THE BIG WAVE

Galeria Filomena Soares, Lisbon – Portugal, 2018

May 10th to September 8th 2018

LIQUID BALLISTICS

Milk by Jeff Wall (1984), is one of contemporary

photography’s most intriguing images. It is also an (unexpected)

entry point into Letícia Ramos’ most recent body of work, currently

on exhibition at Galeria Filomena Soares. In the image, a man

sitting on the floor, with tense facial and body language, projects

the contents of a carton of milk into the air, producing a natural

form with unpredictable outlines: ‘the expression of infinitesimal

metamorphoses’, as the artist describes.

Relinquishing the complex psychological and social

weight that is frequently associated with this image (and with

Wall’s work in general), Milk is the departure point for the artist’s

pivotal essay ‘Photography and Liquid Intelligence’ (1989), in

which he describes the ‘liquid intelligence of photography’ as a

counterpoint to what he calls its ‘mechanical’ or ‘dry’ aspect. If

‘liquid intelligence’ is linked to a possible genealogy of chemical

processes – soak, bleach, rinse, dilute – that derive from a

lost memory of image production; then ‘mechanical intelligence’

is all the ‘ballistics’ that result from the mechanised opening and

closing of the shutter. In the first case, the experimental and

erratic character of the image – where the dream of freezing the

movement of light on the plate wasn’t yet considered (except as

a fantasy) – becomes, in the second case, the codification of

gestures of capturing, preserving and disseminating the image:

the foundation of the ‘modern’ concept of photography.

Ramos’ work is situated in the rare inflection of history

between the nostalgia of early days and modern ‘ballistic’

cynicism (borrowing from Wall’s expression), opening up to a field

of philosophical uncertainty (‘we don’t know if we are the future

of the past or the past of the future’) in relation to things that are

presented to us as ‘pure’ and unquestionable documents. With

a solid path in the art field with prominent exhibitions and prizes,

such as BES Photo (2014) and Instituto Moreira Salles Grant

(2017), Ramos unveils the poetic and fictional side of her many

‘scientific’ projects both through the creation of photographic

devices designed to capture images and rebuild movement and

her creative and experimental research on mediums that are

conventionally seen as ‘obsolete’, such as microfilm. Ramos has

said that she is ‘interested in pre-existing technical possibilities

used for non-artistic purposes and the extent to which they can

enrich experimentation’. As such, Ramos’ work offers a route to

understanding the bifurcated paths of the history of photography,

which restores (and challenges) the ‘merging’ aspect of images:

between chance and accuracy. Alongside a few other artists, she

takes a singular path to explore an affective, aesthetic or ‘liquid’

order through the mechanical and controlled act of producing a

‘reality’.

In her first solo show in Lisbon, Ramos chose a title that

is particularly familiar to us: The Great Wave. Many will remember

that summer at the end of the 1990s when the rumours of a false

tsunami triggered panic in the Algarve and thousands of beachgoers rushed away from the sea. The ‘phenomenon’ – identified

as a ‘dark mass’ on the horizon – was the result of an optical effect

linked to heat. However, this didn’t stop the population, the fire

brigade, the civil authorities, the press and others from publicising

the event as ‘real’. Followers of Ramos’ work are familiar with

her recurring interest in these types of ‘occurrences’, which

has taken the artist to remote landscapes, such as her journey

to circumnavigate the Artic Pole and her ‘historical-mythical’

accounts of earthquakes, including the catastrophic incident

of 1775 (Historia Universal de los Terremotos, Fundación Botín,

2017).

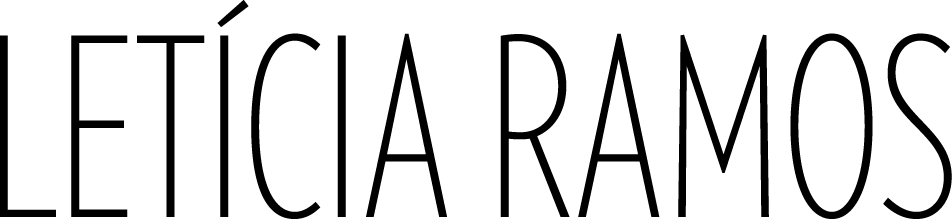

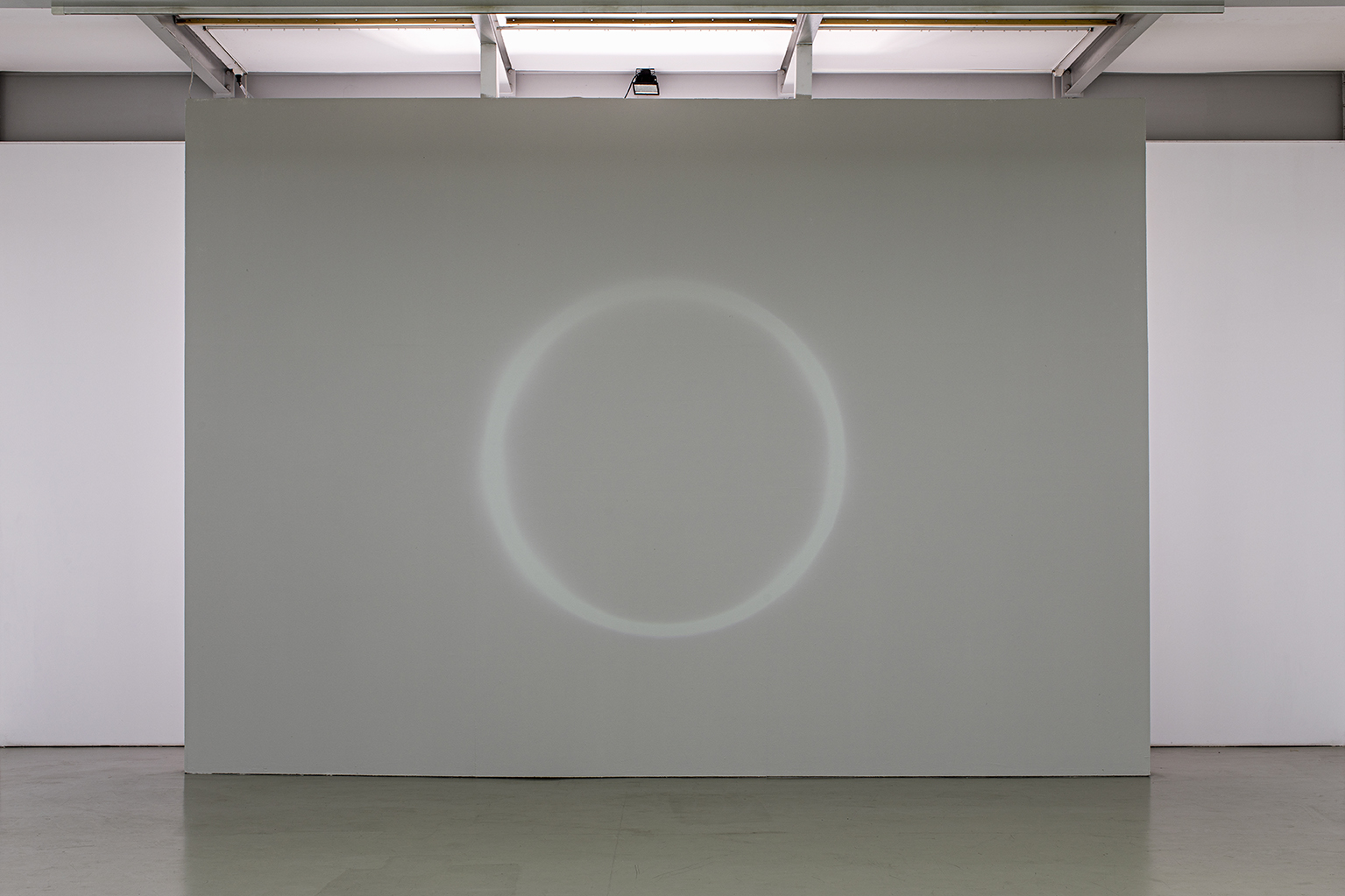

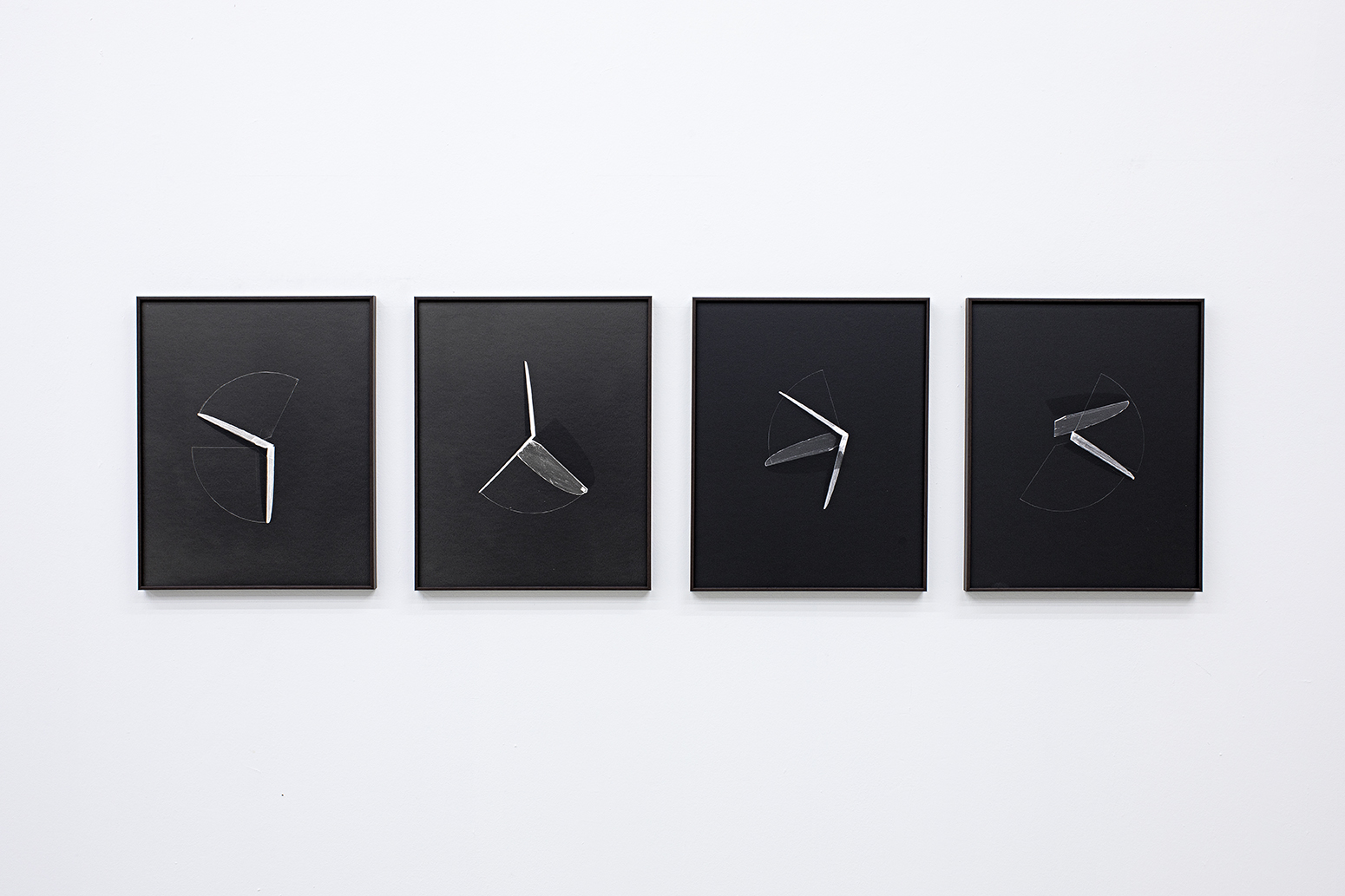

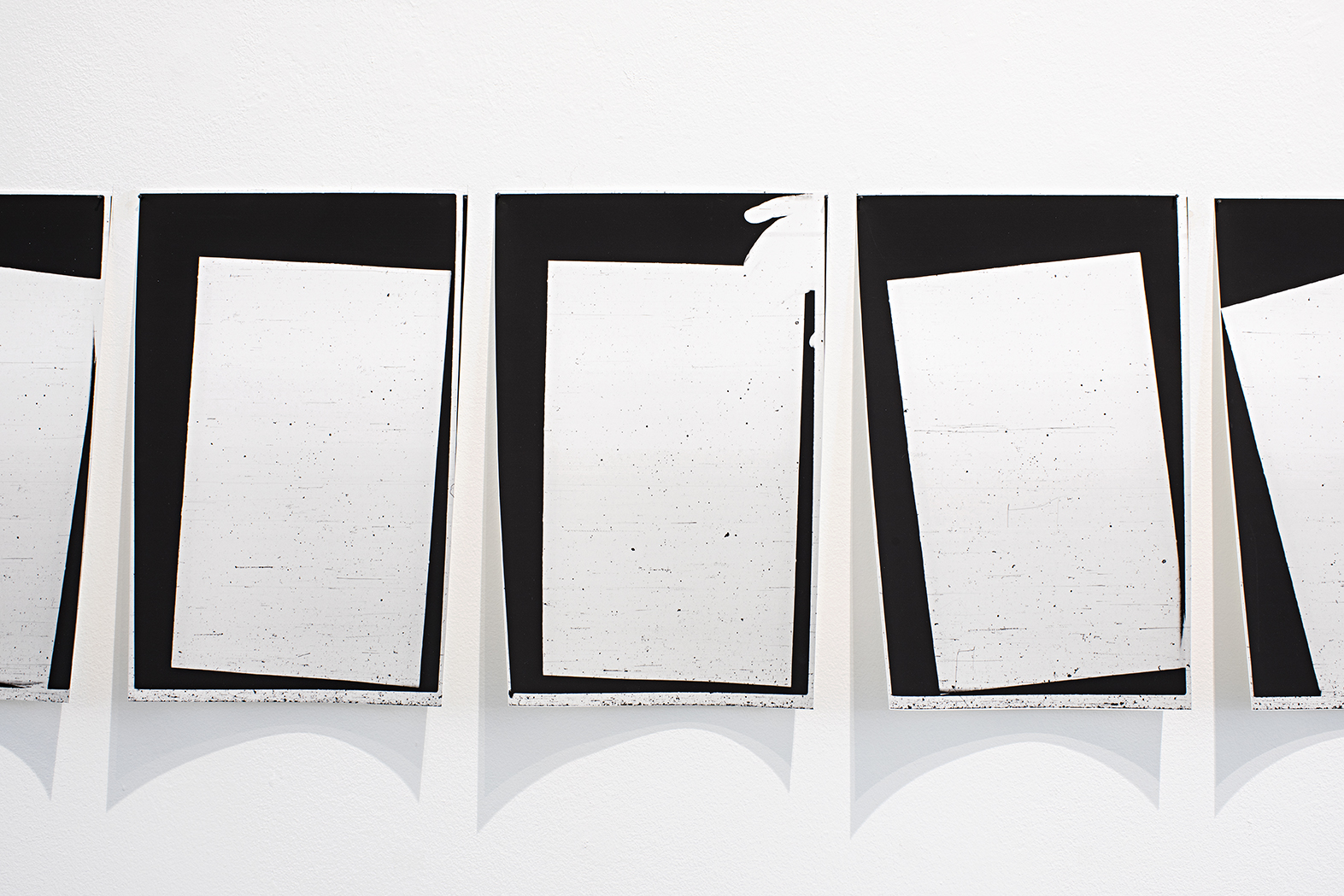

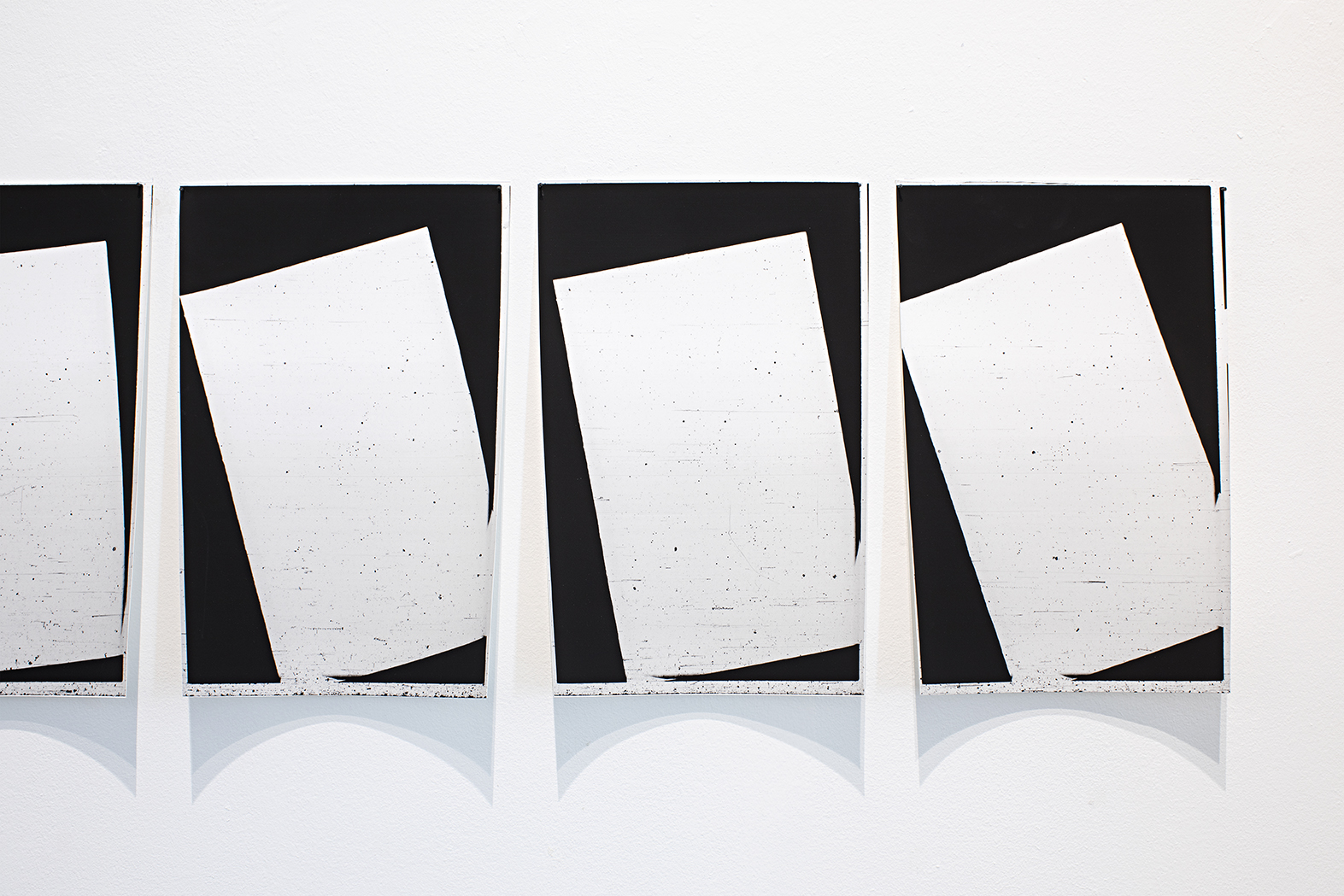

Using a similar approach to other exhibitions that

indistinctly introduce rumours and scientific facts, The Great

Wave explores montage procedures that make us oscillate

between a nostalgic atmosphere and something ‘spectacular’,

analogous to the ‘special effects of a smoke bomb’! Formal

studies on photographic materiality and image construction

without any stage-setting apparatus (‘I am more concerned

with the surface of the photographic paper than scenography’),

such as Carta Branca [Blank Letter], Bicho Branco [White Beast]

or Superfície I e II [Surface 1 and 2), coexist with artworks that

crystallise moments of exceptionality, where the phenomena is

transformed into objects of great poetry, such as Light Photogram

and Fata Morgana. Nonetheless, the conceptual territory shared

between these works is evident and is qualitatively explored in

the uncertainty we feel when visiting the exhibition. In fact, Fata

Morgana condenses this apparent dichotomy and ‘talks’ for the

whole exhibition. It simultaneously refers to the sorcerer Morgana

(King Arthur’s half-sister, who according to legend had the power

to change her appearance) and to an optical illusion produced in

the artist’s studio. The gap that seems to exist between these two

groups of works is in fact a statement in homage to our continuous

ability to use our imagination on the simplest light drawings on

paper. The fact that she is not using any type of camera and that

she produces unique images – as the ones presented here –

reinforces a speculative field that challenges the ‘mechanics’ of

modern photography, its construction and reproducibility.

Going back to ‘Photography and Liquid Intelligence’,

we understand that Wall’s effort to recover the ‘liquid’ is also a

way of criticising the evidence-like status of photographic images

and our idea of history. This is also the foundation of Ramos’

argument, particularly in a time when reality (the ‘event’, according

to Benjamin) is entirely focused on mass transmission. As it is no

longer necessary to look at the world because the camera will

do it for us, The Great Wave takes us closer to historical time

via caesura (or ‘interruption’). But how? By creating an effect of

proximity that places us before the world as if we were there for the

first time. Are the events in The Great Wave real? Yes and no, but it

doesn’t matter: the condition of ambiguity, on the scale of reality, is

applicable to the entire field of photography: the ‘liquid-mechanic’

ontology.

Marta Mestre

2018