2017 - 2018

See the project blog here

In 1775 Lisbon was destroyed after suffering

an earthquake, followed by a tsunami and a fire. This

catastrophic event had a profound effect on the country.

Letícia Ramos starts from this historical event to produce

a non-documentary narrative. This artist has cultivated a

specific interest in “cooking” photography, and has developed

various prototype cameras. Consequently there is a certain

physicality in the experience of images in her work. This

photographic experience immerses us in an idea of the past

through grain and texture. This crossover between science

and craftsmanship, between knowledge and experimentation,

emerges in her various series of works. Historia universal de

los terremotos [Universal History of Earthquakes] (2016-17)

is not a document or a historical review of what happened in

Lisbon; it is a fictional story based on an event which Ramos

uses to weave an experience of her own. Historia universal

de los terremotos is the project she has created for this

exhibition and it includes not only a series of photographs

but also an artist’s book and a sculpture (should we call it

kinetic?), which is related to the gaiola pombalina. This

structure, the gaiola pombalina, was developed in Lisbon as

an anti-seismic construction technique after the earthquake.

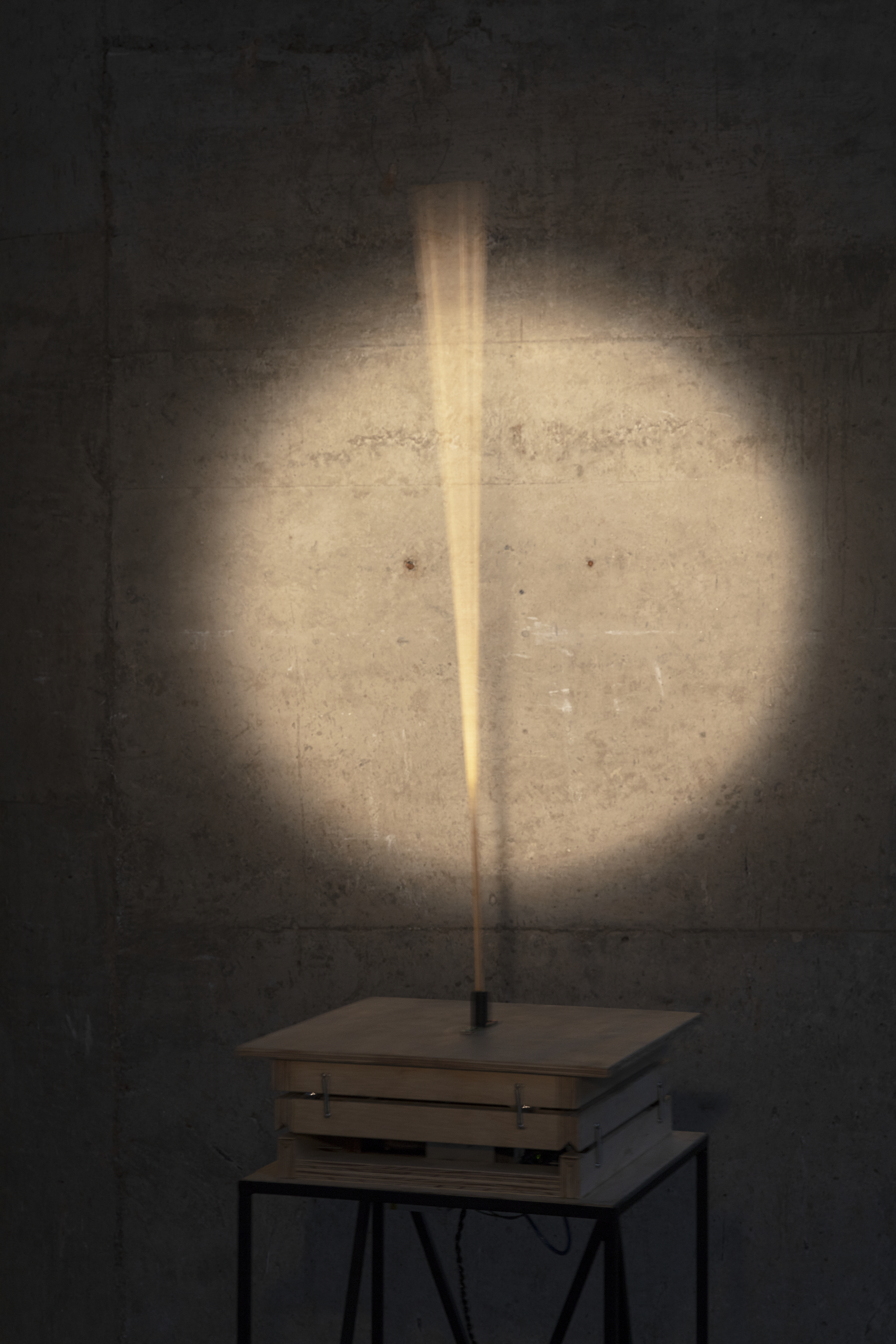

For this photographic series Ramos uses a process

of stroboscopic photography on microfilm with which she

captures the movement of falling objects, in a direct reference

to the impact of the earthquake.

Stroboscopic photography has been used primarily

in the scientific world and has become widely known

through the legacy of Edgerton. Ramos has found a way

of interweaving the natural with the mystical, the force of a

geological phenomenon with the human construction of an

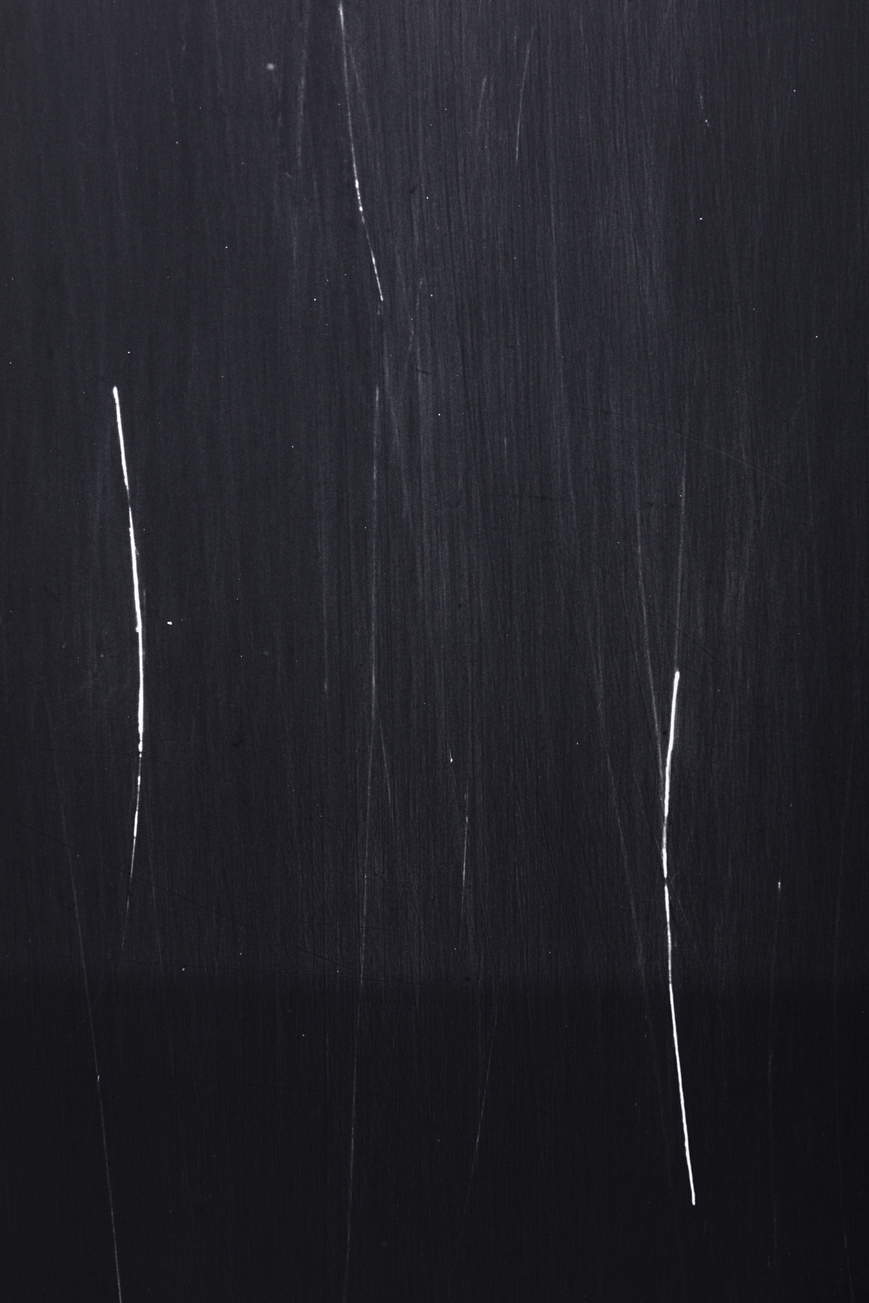

imaginary governed by the irrational. El mago y el terremoto

[The Magician and the Earthquake] (2016) and Espectro del

seísmo [Spectre of the Earthquake] (2016), titles of series

of images within this project, reflect this convergence with

the esoteric. The images, of an abstract nature, reflect the

loss of focus that we imagine in an event of this kind, where

everything loses its sharp outlines and is abandoned to its

natural fate. These images also takes us into the realm of

avant-garde, unlike historical photography. The fascination

with the structure of the gaiola is expressed in a series of

studies in which she analyses the movement of a sheet of

paper failing, also using the stroboscopic technique.

This is not the first time Letícia Ramos has worked in

a hybrid area between science, history and fiction. Each of

the projects is in turn an experiment. Ramos constructs all

kinds of contraptions and machines that will help her carry

out the project she is working on. In 2012 she produced the

Vostok project. Starting from the real event of the voyage of a

Russian bathyscaphe to the Antarctic lake of the same name,

she developed a video in which we see the vessel sailing

through the depths of the lake. As part of this project she also

produced a sound work and an artist’s book.

This reference to the scientific and to frontiers is

something that fascinates Ramos. It is seeing scientific work

as means of generating significant images for creating art; it

is discovering a new and extreme territory in which dividing

lines are erased. Ramos developed this idea of simulating

scientific images in the same period as Vostok with a whole

series of photographs that lead us into this area, with titles

like Teleportation (2014) and Meteorite I (2014), although in

fact they lack and scientific meaning and only make sense

in the artistic sphere. In these works she not only introduces

the notion of simulation in the strict sense, but also the idea

of simulating utility in an ontological sense. Together with

these concepts, the idea of photographic technique is an

ontological sense. Together with these concepts, the idea

of photographic technique is an intrinsic element of her

work. Ramos has constructed unique hand-made cameras,

enabling her to create images distinguished by the notion

of singularity. These inventions of technological archaeology,

the “Escafandro” [Diving Suit], the “ERBF” machine, the

“Polar”, which she developed between 2007 and 2012, are

devices she uses to create unique images that somehow

swim against the current of the contemporary digital world.

Text from the catalog “ITINERARIOS XXIII”

2017

INDUCED EARTHQUAKES ARE ALSO UNPREDICTABLE

In Japanese mythology, the god Kashima is in charge

of guarding Namazu, a giant catfish, keeping it inside a stone

cave in the depths of Earth. When Kashima lets his guard

down, the fish escapes and the movement of its tail causes

earthquakes across the planet. This is one of the stories in

Leticia Ramos’ collection. The artist has been investigating

the socioeconomic, psychological and political causes and

effects of earthquakes since she was awarded the Fundación

Botín Visual Art Grant in 2016. The departure point for her

research is the earthquake that struck Lisbon in 1775. Seen

as one of history’s most intense earthquakes, the event had

a tremendous impact on 18th century Portuguese society –

and, consequently, also on its colonies. The cataclysm (the

earthquake was followed by a tsunami that generated waves

up to 20 metres high, as well as countless fires) hit Lisbon in

the morning of All Saints’ Day, endorsing the many mythical

and religious interpretations of the calamity that followed. The

Marquis of Pombal – who was then the country’s Prime Minister

– was in charge of rebuilding the Portuguese capital. The

nobleman erected the metropolis’ new structures at a speed

that would cause envy to contemporary developers who are

today responsible for the contentious projects of retrofitting

these same buildings. The enterprise was mostly paid for by

gold coming from Minas Gerais, and it required a monumental

amount of timber – for instance, the famous ‘Pombaline

cages’ , were built mainly using Brazilian hardwood – which

was imported in a rush from the Brazilian colony, triggering

commotion amongst taxpayers across the Atlantic.

Ramos draws on this traumatic event in order to

produce a sequence of static and moving images that are the

result of multiple photographic experiments. Since the start of

her career, the artist feeds a specific interest in procedures

and the historical evolution of analogic photo-techniques,

which has led to the development of a series of unique

devices and machines that are able to materialise her projects.

‘Universal History of Earthquakes’ is the combination of of a

deep understanding of the media and the artist’s interest in

narrative – in this case, both historical and fictional. Narrative

is often an intuitive tool used to mitigate the impact of drastic

changes: we tell stories to ourselves and create characters

and allegories in order to give sense to the intangible or to

make the experience of reality more tolerable.

The earthquake hit Lisbon in 1775, and photography

was invented in 1835 (somewhere between the historical

disagreement about its authorship: Talbot or Daguerre?).

It was precisely the lack of ‘photographic evidence’ that

encouraged the artist to investigate the accounts of that time

through stories told by those who were keen to narrate and

visually represent what the saw. The majority of photographs

exhibited in ‘Universal History of Earthquakes’ were created

using the technique of stroboscopic photography in microfilm,

which registers the movement of falling objects, in a direct

reference to the moment when the shaking occurs. By

employing techniques that are typical of the scientific field,

Ramos transposes the experiences of a technical lab to the

photo lab, creating, therefore, a new type of visual vocabulary.

A sphere cuts through a black plane, gradually

losing its definition; its dilated displacement is somehow

melancholic, soundless (The magician and the Earthquake

I, 2016). The images of earthquakes that we often thing. Her

visual simulations fascinate for the way they reiterate the

mystery and speculation that still reside in the most advanced

scientific discoveries. There is still no convincing explanation

about the reasons behind the movement of tectonic plates –

perhaps Kashima’s unintentional nap that allowed Namazu to

escape. On the face of it, all we can do is study their impact

and project potential preventive measures (such as in the case

of Pombal’s constructions) or to turn this kind of phenomena

into allegories that can illustrate the socio-political mess we

are in.

The legend goes that Namazu only escapes when

social injustice is rampant. It levels things out and, faced with

the tragedy, everyone goes back to ground zero. In calamitous

situations, the State is put to the test, whilst cooperation

and solidarity networks come to the fore. Immanuel Kant is

amongst the several Enlightenment philosophers (Voltaire

refers to the earthquake in Candide, for example) who tried

to understand the possible reasons behind nature’s ‘furious

wrath’ against Lisbon. The German writer chose a geological

and moral argument to approach the catastrophe, thus moving

away from the divine explanations that were prevalent at the

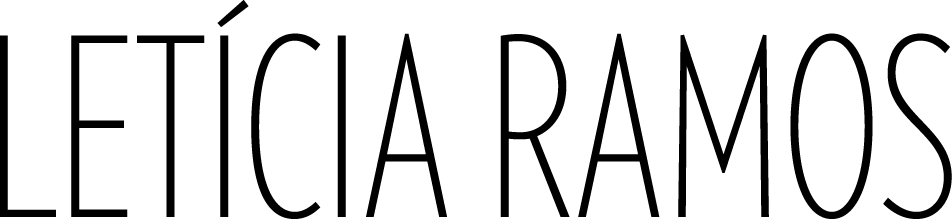

time. With this in mind, Ramos took her proposition further by

acting out ‘empirical science’ . At Pivô, the artist replicated the

experiment proposed by the philosopher in one of his essays

about the natural disaster in Lisbon. Ramos used boxes filled

with soil built according to the following instructions:

‘It is now time to say something about the causes of

earthquakes. It is easy for a natural philosopher to reproduce

their manifestations. One takes twenty-five pounds of iron

fillings, an equal amount of sulphur, and mixes it with ordinary

water, buries this paste one or one-and-a-half feet underground

and compresses the earth firmly above it. After several hours,

a dense vapour is seen rising; the earth trembles, and flames

break forth from the soil.’

Taking Kant’s speculation to create a fictional film,

Ramos pushes scientific narrative beyond its limits. Today, the

‘natural philosopher’ to which Kant refers is closer to an artist

than a scientist. The concept behind the experiment does

not explain the origins of earthquakes but it encompasses

the conflict between religion and natural science at a crucial

moment in the history of Western thought. And what does it

mean to talk about earthquakes – or images of earthquakes

– in an art exhibition in Brazil in 2018? Whilst I was writing

this text, I received a phone alert from The Guardian telling

me that an earthquake had just killed 98 people in Bali. I

opened the link and watched shaky video footage shot by

an eyewitness on their phone. The muffled audio revealed

screams and explosions. I attempt here to answer my question

with another question: why did the English newspaper choose

to publicise precisely this image? Perhaps because it is a

‘real-time’ illustration of the horrors of a natural catastrophe

and, in the same measure, a solid evidence of the paper’s

efficient coverage. I am thousands of miles away from the

quake’s epicentre and yet I promptly received the news

seconds after it had happened. In the era of hyper-definition,

the amateur image adds a sense of truth and urgency different

from professional lenses. Hito Steyerl coined the term ‘poor

image’ to describe this type of image. For Steyerl, these

inferior images, made in a rush, carry some weight of reality

and are conducive of a certain aesthetic of objectivity that is

symptomatic of our time.

The ‘aesthetic’ of a shaking camera has been coopted by the mainstream media – and, of course, this makes

room for induced situations and scenarios. The only thing that

makes me believe that the video was in fact shot by someone

who was amidst the earthquake in Bali is the newspaper’s

logo that appears at the corner of the screen. However, in

reality, the video could have been made in someone’s shower,

in the same way the first landing on the moon could have been

staged using a model similar to the ones produced by Ramos.

Her complex analogic images do not echo Steyerl’s concept.

In contrast to the images which the German artist refers to –

which are like a digital and frantic by-product of the search

for absolute present in our advanced capitalism –, Ramos’

photo-experiments insist on the idea that there is something

important about the images that take long, that do not speak

for themselves. They are not evidence or a symptom of

anything, deliberately remaining as an open question. Ramos’

images are premeditated manipulations, which in a sense

makes them immune to the conceptual reconfigurations that

images in circulation are often subjected to.

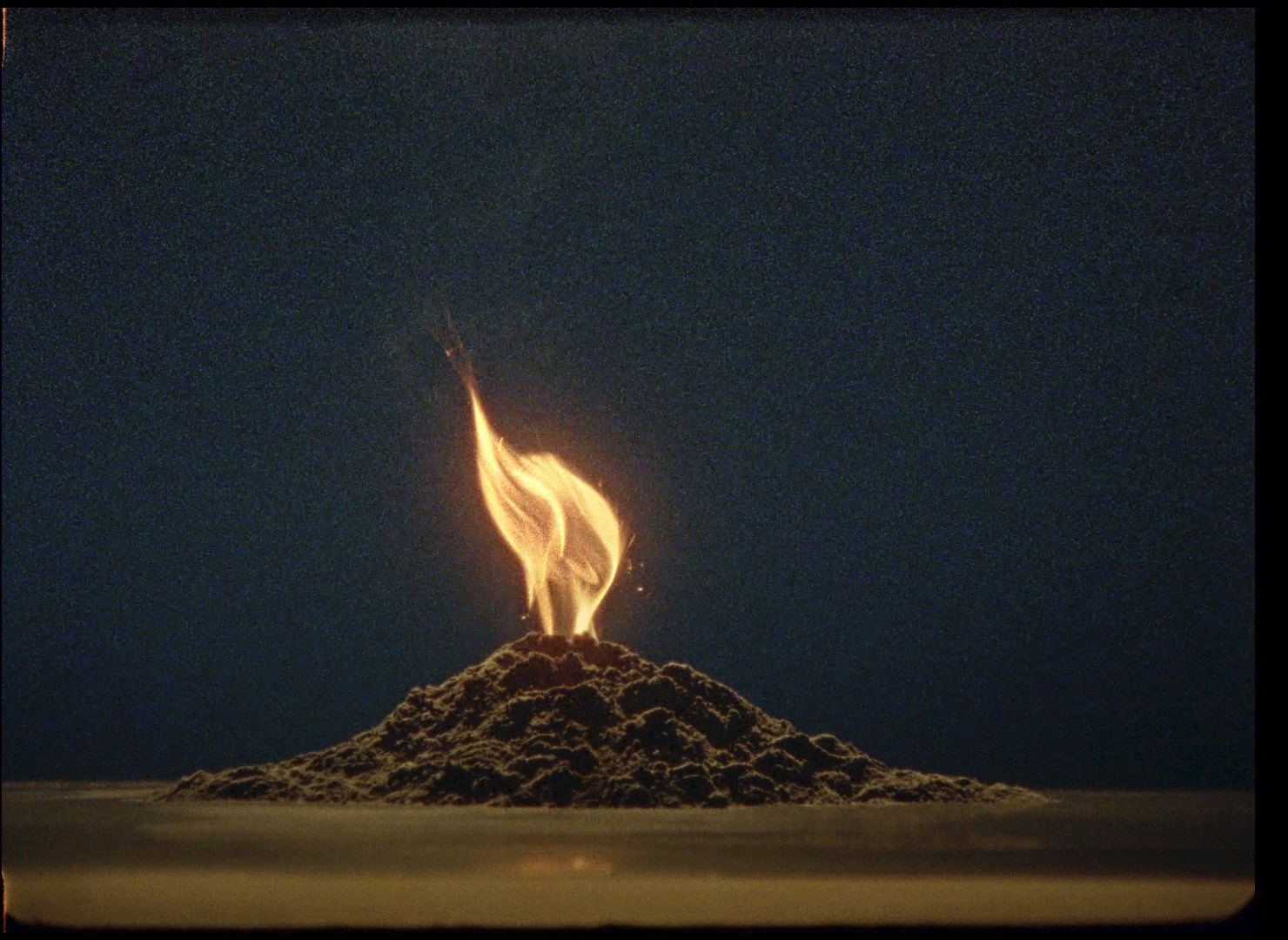

Ramos’ historical-scientific-fictional research evolves

into the installation Seismograph (2018). By transforming a

16mm projector into a mock seismograph, the artist proposes

to measure and, simultaneously, project the vibration of the

Copan building. The metal needle that scratches the negative

exposed in real-time supposedly reveals the modern building’s

vulnerability – or perhaps the vulnerability of all structures we

believe to be stable. And what does that mean in seismologic

terms? Absolutely nothing. This new cinematographic

machine expands on the approach that Ramos has taken for

years: a phenomenon, a historical event or a piece of news

is the departure point for long and comprehensive projects

of artistic investigation. Still today we think about the impact

of Lisbon’s earthquake, we understand the extent to which

it affected the relationship between Portugal and Brazil, we

also know that its ramifications propelled Enlightenment

ideas and have provided us with a legacy of civil construction

techniques and geological research. However, despite it all,

it is still impossible to predict an earthquake. Therefore, an

earthquake is always something imminent. Leticia Ramos’

work inhabits a place between science, history, fictional

narrative and (why not) magic – a place that is only accessible

to art. Her open projects look attentively to the effects of the

past without worrying about predicting the future. This artistinventor calls our attention to the fact that an image is always

the merging of something in the world with our ability to

interpret and transform what we see.

2018

“Universal History of the Earthquakes”, Pivô - Art and Research - São Paulo, Brazil, 2018

“Itinerarios XXIII”, Fundación Botín, Santander, Spain, 2017